One popular sentiment among tournament Scrabble players is that passing is always a bad play: that you are always better off exchanging or making a play whenever possible. As a general rule of thumb, this is definitely true: passing is very rarely the correct play, as it scores zero points and doesn’t improve your rack. Usually there is at least a tile that you can exchange, and if your tiles are not any good this rack, what makes you think they’ll be any good on a future rack.

However, like any rule, there are exceptions. Make no mistake, these exceptions are rare, and for the most part, only high-level players should ever do this, since by and large, passing is generally a mistake and most players do it far too often. Even when done by top players, passing is less often an optimal play and more often a play that is hoping your opponent is going to make a mistake. Most of these exceptions come towards the end of the game, however, there are some rare times when passing is acceptable in other situations. This page will discuss the many appropriate applications of passing your turn, both.

Before we start, it’s worth noting that the most frequent time to pass should actually be when a good opponent passes. Most of the time when your opponent passes, they are hoping you make a mistake: passing is seldom (although sometimes) optimal. If a very strong player passes, alarm bells should be ringing through your head, and something bizarre is going on.

When in doubt, if someone passes, your first instinct if you don’t know what to do should be to pass (or exchange), and this way it’s unlikely you get exploited by your opponent. This holds true whenever a strong opponent does something that seems crazy: they’re almost always thinking *something*. It’s very rare that passes are optimal: more often they are actually gimmicks seeking to induce mistakes.

With that in mind, let’s look at some situations where passing could be a reasonable play:

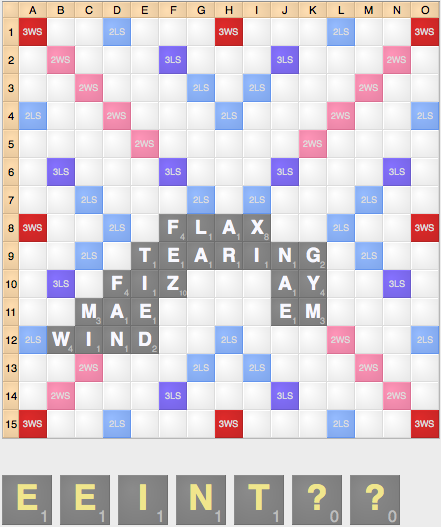

Endgame

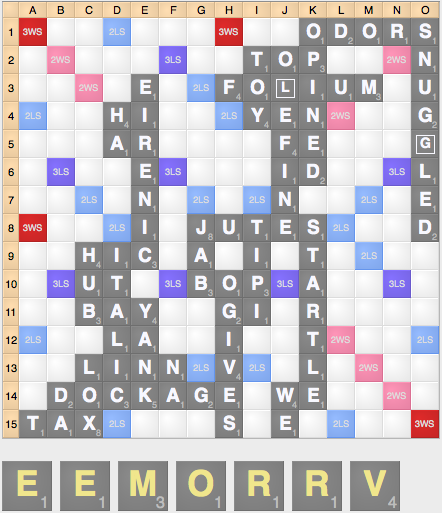

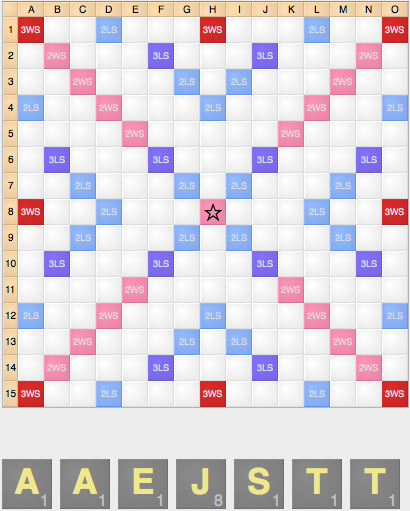

Pool: GINOOZ

Pool: ABEINOZ

In this position, your remaining R and T can both limit or prevent opponent’s Z setups. While you’ll never score more than the 22 points from WHORT with those tiles, the defensive capacity of those tiles make passing a better option.

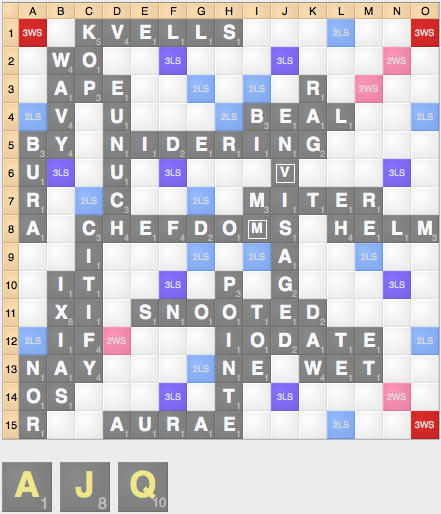

Situation 3. When your opponent often has to make different plays in response to your remaining tiles (i.e. QIS doesn’t play, but lots of options create QIS)

Pool: DEINORU

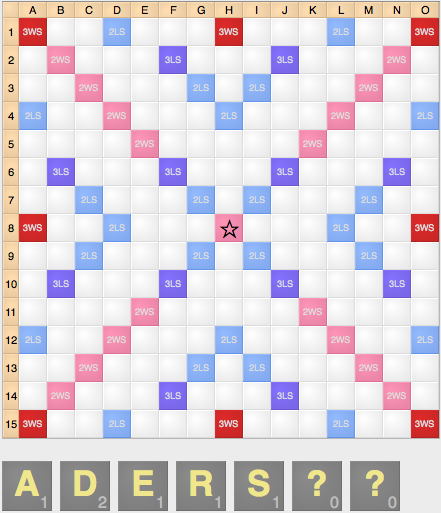

Pre-endgame

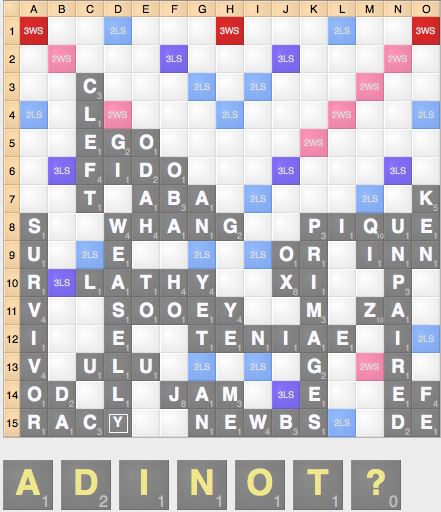

Score: 386-357

Pool: AAEEOQRSZ

Score: 386-357

Pool: AAEOQRSWZ

It doesn’t even matter if you have a bingo: you still need to pass in these sorts of circumstances. The additional 50 point bonus won’t save you from the consequences of playing a trap endgame with the Q.

It’s worth noting that if you’re the opponent, if your opponent is passing in these circumstances, you will usually be better off on spread by passing back. This should lead to an occasional game where the bag is never emptied, and the game will simply end on 6-passes. However, be careful, as a particularly tricky opponent might start passing with the Q in hand.

Situation 2. When the score is such that you need your opponent to empty the bag.

Score: 398-395

Pool: EIORRSTT

Situation 3. When your opponent is likely to empty the bag and almost never blocks your spot

Score: 449-408

Pool: CEFIIIMOR

In this position, there’s very little chance that the I in row 1 is getting blocked, even if you pass, as doing so will score very few points and cripple your opponent’s rack. Meanwhile, playing a bingo immediately isn’t so great, as II draws or potential C sticks could lead you to lose a lot of spread. Thus, passing is viable, hoping your opponent plays so you can bingo out.

It’s worth noting that your opponent could just pass back, but then you can always play the bingo later. It’s essentially a freeroll. Passing back is always a viable counter-strategy, but it doesn’t put your opponent at an advantage. It’s also worth noting that your opponent can play off one tile, but that mitigates the II draws, makes C sticks less likely, and again, you still have the option to pass.

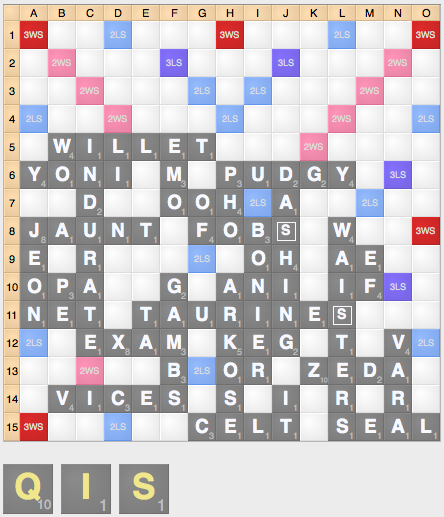

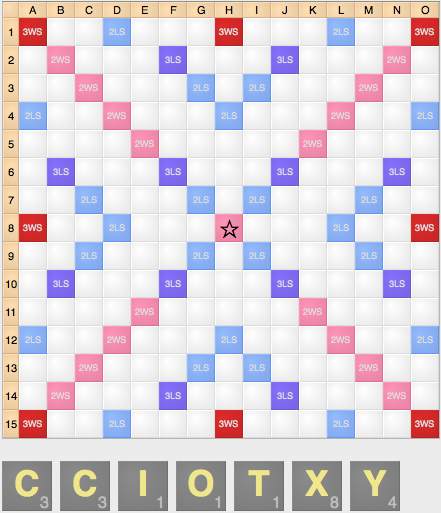

Situation 4. When you think passing can induce mistakes.

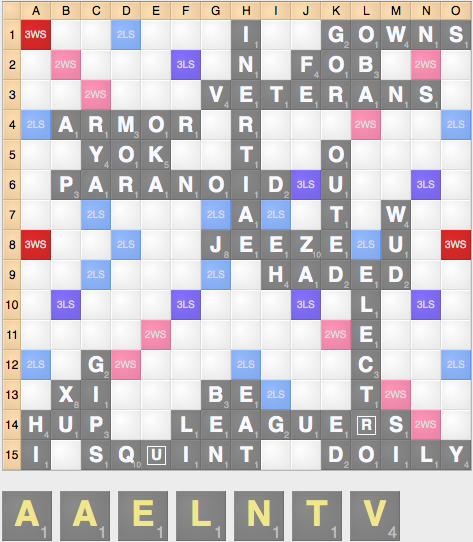

Score: 384-342

Score: 384-342

Pool: EEHORSW?

In this case, your opponent has the word SHOWERER/RESHOWER regardless of what’s in the bag, as well as NOWHERES at c8. In short: you’re in a lot of trouble, and if your opponent plays perfectly you’re totally dead: hardly a good proposition. However, you might be able to bailing yourself out by passing, and trying to induce your opponent to make a mistake by playing a bingo immediately, or make some sort of odd defensive play that allows you to win. This strategy can be effective as your opponent might feel forced into playing the bingo, especially if the blank or S are in the bag.

Against good players, you might want to avoid this, as your opponent can deduce your entire rack and react accordingly, thus eliminating any winning chances you might otherwise have. Good players can figure out the only racks you might have that make any sense, thus completely overriding any potential benefits that passing might have in these sorts of instances. This concept of deducing an opponent’s entire rack is also known as superimplication.

Situation 5. When there’s one in the bag and your opponent has to empty it.

Pool: ADILLOPU

In this case, you have a bingo in two spots, but you have to draw the last tile in the bag. In this case, you can gain some spread by passing, letting your opponent play and drawing the last tile in the bag, then playing a bingo out. Your opponent can do little to nothing to prevent this tactic other than pass back, making this position another freeroll.

Situation 6. To induce your opponent to open a 3×3 (can rarely occur mid-game).

Opening Rack

Passing three times with a rack like this makes a lot of sense, as your opponent is somewhat likely to pass three times and end the game. Even if they only do so 30% of the time, this is still a net positive result for you.

Situation 2. When you’re using the threat of the 6-pass rule to force your opponent to give you a tile for an 8 letter word.

With this rack, you can play a bingo and hit the TWS with 4 of the vowels played on the center star with VIRTUOS(A/E/I/O) and bingo with the last one (VIRTUOUS) making it a strong candidate to pass with on the opening rack.

It’s worth noting that with both of these racks, you need to be willing to go the distance and pass three times, risking a 6-pass loss. If you’re not willing to take that risk, you shouldn’t be passing in the first place. Because of this, you should pass extremely rarely with this type of rack.

(Counter-strategy: Open short off-center)

Let’s say that your opponent has passed, you’ve exchanged, your opponent has passed, and you exchanged again, and your opponent has passed for a third time and you have this rack. This is not a rack you want to pass with, or even exchange 1: it’s not a strong enough rack. You probably want to play the word TAJ, however, your opponent is likely to use the A to play a bingo, often hitting the 3WS. Because of this, you actually don’t want to play TAJ at 8g like normal, but rather you want to open off center: playing TAJ at 8h to reduce the score of your opponent’s likely bingos. This is the best way to defend against opponents using a passing tactic, as it limits their ability to really punish you since they will primarily focus on vowels you might open to play a bingo.

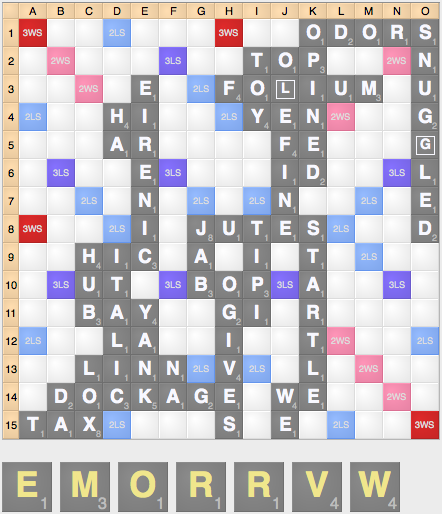

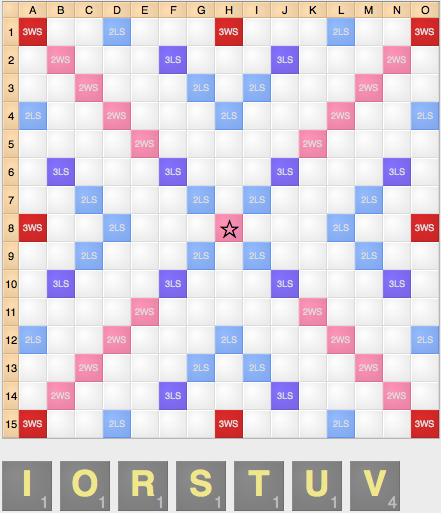

Mid-game

Situation 1. When you have a lead and most of your opponent’s plays will give you bingos that score significantly more than your best play.

(Counter-strategy: Open 8s primarily, but be balanced)

Situation 2. When your opponent will make a specific word very often that opens a 9 (so unbelievably rare, not sure this has ever happened before)

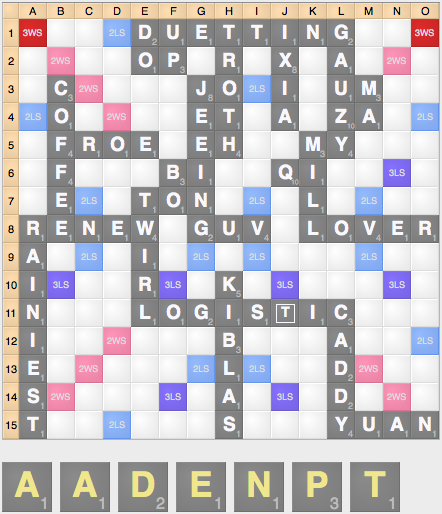

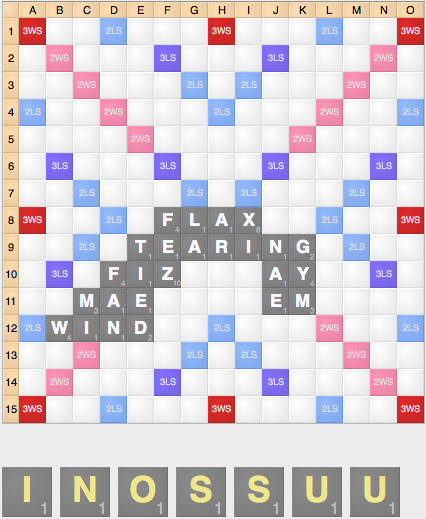

Score: 296-253

Pool: AADEEEEGHIIIIIIMNNRRRRSSW?

In this example, you’re ahead by 40 points, but your opponent has traded 5, likely with either the blank or the S. The board is extremely closed. While you can play something like FLOAT, you can also pass, as your opponent is extremely likely to play XI next turn, allowing you to play AFLATOXIN. While your opponent *might* be able to figure this out, it’s much more likely that a) they won’t see the possibility at all, or b) they think that you just have a bingo rack of some sort and hope you’ll open the board through them.

This situation will happen about as often as winning the lottery.

Situation 3. When your opponent has played a phoney.

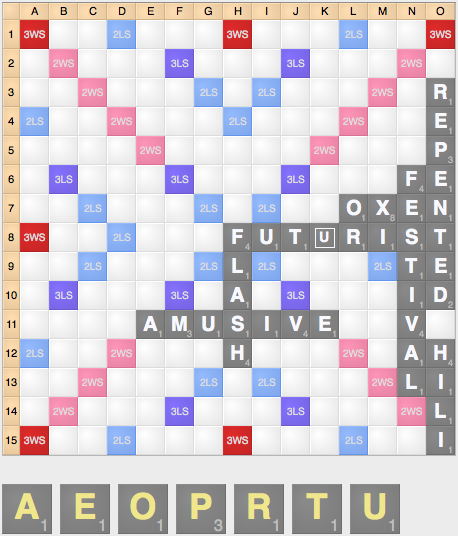

In this position, your opponent has just played QUAILIER*, which you have challenged off, but you’re holding a rack (AEOPRTU) which bingos through the Q. While you could make a 25 point play, most of your opponent’s plays will give you the Q to make a high scoring play, including QUAIL for 50, which will give you a 3×3 next turn. While you might occasionally be outmaneuvered by a play such as LIQUOR, most of the time you are going to end up with a bingo if you pass instead of play on your next turn. (Note that you can also consider a phoney that doesn’t expose most of your rack, such as TAEL/FESTIVALE*) that you hope gets challenged off. It just depends on how suspicious your opponent will be.)

Situation 4. When the board is near gridlock and you’re ahead, you have no good plays, and you have no good tiles to exchange.

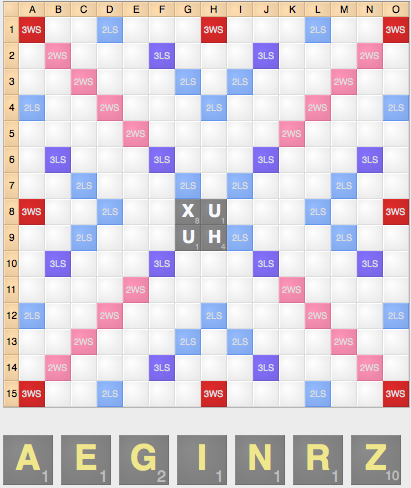

Score: 21-18

Last play: Opponent exchanges 5

In this position, your only real options are exchanging the Z or passing. Passing is better as your opponent should respond by giving you a good Z play or a bingo a very large percentage of the time. Since the Z is better than an average tile in this position, you should pass since there is no good way to improve this leave and you don’t mind this game going to a 6-pass scenario (on the 6th pass, simply exchange your Z.)